The North Shore vs. Dutch elm disease

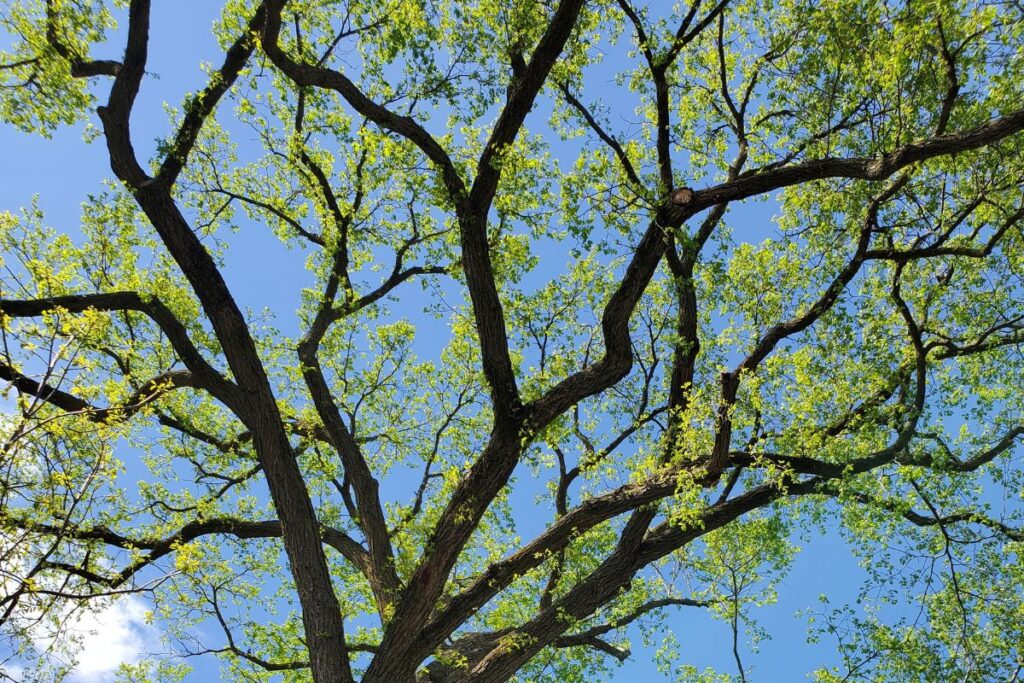

They are loved for the lush and shadowy canopy they cast over roads and city streets; they’ve been mourned as those canopies disappear like green mist, destroyed by the incurable fungus known as Dutch elm disease.

Elm trees on the North Shore didn’t escape the disease, and when it hit, it hit hard, according to foresters who work with local communities. That’s because elms, largely American elms, were planted extensively around private homes and on public land and right of ways by that time, rendering the entire population vulnerable by virtue of proximity.

Now Kenilworth resident Greg Kirrish is asking people who love elm trees and who might still have them on their properties, to get them inoculated against the fungus. It might not save every tree, but it’s worth trying to do so, he said.

He also wishes that Kenilworth and other North Shore communities would do two things: protect elms on public property and take steps to educate residents about Dutch elm disease and how to deal with it on their own properties.

“It’s an education thing, and that’s important,” he said.

The unhappy history of American elm trees and Dutch elm disease goes back to the 1930s, according to information from the Morton Arboretum.

The trees can live 175 to as many as 300 years, according to the United States Department of Agriculture; although Wilmette forester Kevin Sorby said urban elms live much shorter lives, due to pollution from road salt and stressors like poor soil. And according to arborist Dave Coulter, a researcher at Cornell University even estimated the average urban tree lifespan at an astoundingly short seven years.

Dutch elm disease is more than a stressor. It’s a fungal pathogen that attacks the vascular systems of many elm species, especially American elms. It spreads above ground thanks to at least two species of beetles that carry the fungus with them when they burrow under tree bark to feed. It also spreads through interconnected root systems of elms planted in close proximity, something that happens in stretches of urban planting. One infected tree on a city block can quickly spread the disease.

Kirrish has lived in Kenilworth for 25 years with his wife, Kathryn. Their Melrose Avenue block still boasts elm and other trees, in part because he and neighbors such as Eric Miller have taken preventative care of the elms on or near their homes.

Kirrish has always loved trees, calling himself an avowed tree hugger and joking, “I had a sister that claimed I must have been a tree in a past life.”

He cherishes all trees, but he is particularly fond of elms, something he said might stem from his youth in Rockford, Illinois. That city’s streets were once lined with elms and other trees, most of which have disappeared, he said.

Miller pointed to areas on or near their block, where elms once grew but are now gone. He, too, mourned the village’s overall loss, saying, “There were so many elms when the Dutch elm hit that it quickly changed the way things were around here.”

In Kenilworth, where homes often sell for more than a million dollars, many owners seem to balk at the much smaller price they could pay to regularly inoculate their trees, Kirrish said.

“It’s my cynical experience in the world, that people are driven by economics,” he added. “If so, if you’re driven by economics, you’d think you’d be taking care of this.”

David Taylor is a licensed arborist with Hawthorn Woods-based Sunrise Tree Service who has treated Kirrish’s large tree. He treats trees on private properties and has worked with area municipalities to care for public trees, including elms.

“Generally the larger American elms, people want to protect them,” he said.

Owners can minimize the chance of infection by inoculating their trees every two or three years, he added, with the caveat that treatment depends on the tree’s size, health and apparent spread of the disease, and that treatment can’t provide absolute protection. (Information from the University of Minnesota Extension service states that if the disease is caught early, it can be treated by pruning dead or flagging branches, followed by regular anti-fungal inoculations.)

If cost is a consideration, Taylor said, it’s best to estimate the height, breadth and trunk diameter of the tree to get a good idea of the final bill, since costs generally run between $18 and $25 per inch.

Taylor said it’s possible to fight the fungus’s spread through trees’ root systems if owners are willing to take action such as cutting a trench between infected and noninfected trees; he helped a Winnetka property owner do just that, he said.

Winnetka forester Andrew Lueck estimated that the village still has a large number of American elms; his records indicate that includes roughly 250 on public parkways. He said Winnetka injects publicly owned trees on a regular schedule and recommends the same strategy for private trees.

Not all arborists agree. Coulter, who owns Oak Park-based Osage Inc., works with Kenilworth’s public works department on tree care. He is skeptical about inoculation strategies, saying that committing to a never-ending cycle of chemical protection may not be what tree owners should do: “If you’ve got an American elm in your yard, and it’s 100 percent healthy, you probably don’t have to worry. Just keep an eye on it.”

If property owners want to maintain their trees’ health, they should evaluate them in early summer for dead wood, or for leaves near the tree top that are yellow and brown, a process known as flagging, Sorby said. Coulter and Lueck echoed that. All three rendered a tough judgment; a tree with significant signs of the disease should probably come down.

Coulter said that investing too heavily in monoculture, the public and private planting of only one tree species, was nearly a death sentence for another species: ash trees, thousands of which fell to the insect attack of the emerald ash borer.

“We loved elms because of their shape. Then we replaced it with another monoculture,” he said. “One thing I hope everyone’s learned is that now the rule of thumb is don’t plant more than 10 percent of any one species.”

American elms have been successfully hybridized with Dutch elm-resistant elm species, he said, adding, “There are a lot of good hybrids out there, developed decades ago.”

Meanwhile Kirrish urged everyone with elm trees to consider how much they can add in material and other ways.

“They’re incredibly important for aesthetics, water management, for wildlife, for cleansing the air … even for shade. If people can’t [care for their own elm trees] how are we going to stop global warming?” he said.

The Record is a nonprofit, nonpartisan community newsroom that relies on reader support to fuel its independent local journalism.

Become a member of The Record to fund responsible news coverage for your community.

Already a member? You can make a tax-deductible donation at any time.

Kathy Routliffe

Kathy Routliffe reported in Chicago's near and North Shore suburbs (including Wilmette) for more than 35 years, covering municipal and education beats. Her work, including feature writing, has won local and national awards. She is a native of Nova Scotia, Canada.