‘Glencoe Black Heritage’ opens up on the good and bad racial past of the community

The story of Glencoe is incomplete without inclusion of the constant and foundational contributions of people of color.

For more than four years, the Glencoe Historical Society has focused its research on identifying, sharing and cataloging those contributions to ensure their rightful place in the town’s historical record.

“It’s a big project because our Black community began in 1883, 1884,” said Karen Ettelson, co-president of the historical society’s board of directors. “We started chronologically and worked our way toward the present. We’ve worked very hard … but you never really finish. We never want to say we’re done, but we did reach a point where we had a lot of information and stories we could tell the community.”

The society unveiled its findings in its exhibit, Glencoe’s Black Heritage, which debuted during a fundraising gala on Sept. 17 and welcomed its first tours on Sunday, Oct. 2.

The exhibit stretches between multiple galleries in the historical society’s two buildings at 375 Park Ave., and primarily works chronologically, beginning with 1883 through World War I, including a gallery focused on Glencoe’s first black settlers.

One diversion from the chronology is the gallery dedicated to St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church, a cornerstone of Glencoe’s development then and now.

“St. Paul really is a building block of this community,” said Pastor Katrese Kirk McKenzie, of St. Paul, who participated in the curation of the exhibit. “I’m really excited about this. There is a wonderful opportunity with this exhibit to really highlight stories that are important to our community.”

Local icon Homer Wilson, recognized as Glencoe’s first black homeowner, started a prayer group in 1884 and called it Glencoe African Methodist Episcopal Church. Soon, Wilson’s group joined with the AME denomination and purchased property at 335 Washington Ave., the present site of St. Paul AME in Glencoe.

My greatest desire is this (exhibit) is the springing board to tell so many other untold stories that are wrapped into the tapestry woven into Glencoe.”

Pastor Katrese Kirk McKenzie, of St. Paul AME Church in Glencoe

St. Paul’s impact remains significant — and not just in Glencoe. It is the only African-American church along the North Shore, a region that is disproportionately white, but not the only one in the suburbs. Yet, Kirk McKenzie said, church members from all over come to Glencoe for service.

“Members come from the South Side, Buffalo Grove, Zion and more and they pass so many churches along the way,” she said. “Why do they bypass all those other churches? Because they resoundingly heard there is something really special here.”

The exhibit highlights the inclusivity and accessibility of early Glencoe, which unlike many of its neighbors had integrated schools “since Day 1,” Ettelson said. She called Glencoe a “melting pot” prior to WWI and said the research showed that community leaders promoted education and jobs for people of color post-Civil War, and land across town was affordable.

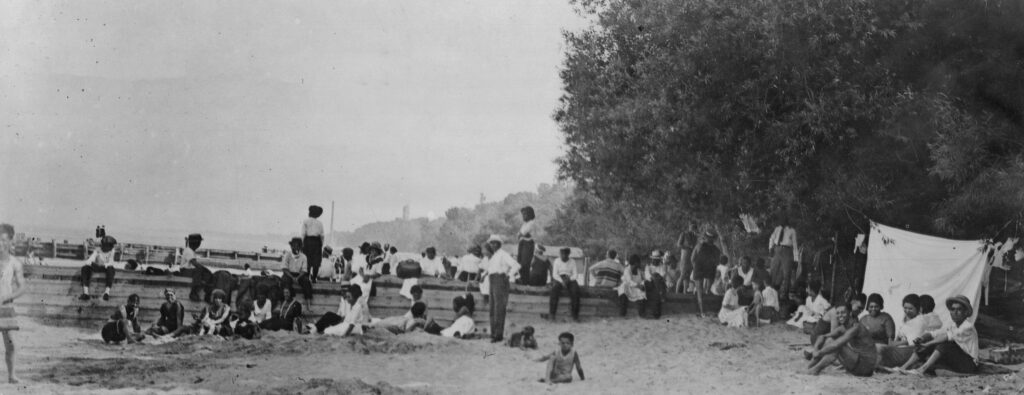

But racist behavior did not elude Glencoe and some examples are brought into the light in the back building of the historical society. In the 1920s, discriminatory housing practices — by the Glencoe Homes Association, among others — worked to keep property away from Black buyers. The association, for instance, would buy up lots in Glencoe and sell them to white homeowners. Glencoe also had a segregated public beach until 1946, when A.L. Foster and his family won a suit in federal court to integrate the beach.

According to the U.S. Census, Glencoe’s Black population of 676 in 1920 shrank to 313 by 1930 and was only 176 in 2000. The latest census numbers (2020) show the Black population of Glencoe is at least 226 residents.

“The world changed a lot after World War I and so did Glencoe,” Ettelson said. “The period in 1920 through a lot of the 1930s, where there was activity that directly impacted the Black population in south Glencoe, was a dark time for the community.

“We wanted to, in our exhibit, be honest and open with the facts of what happened.”

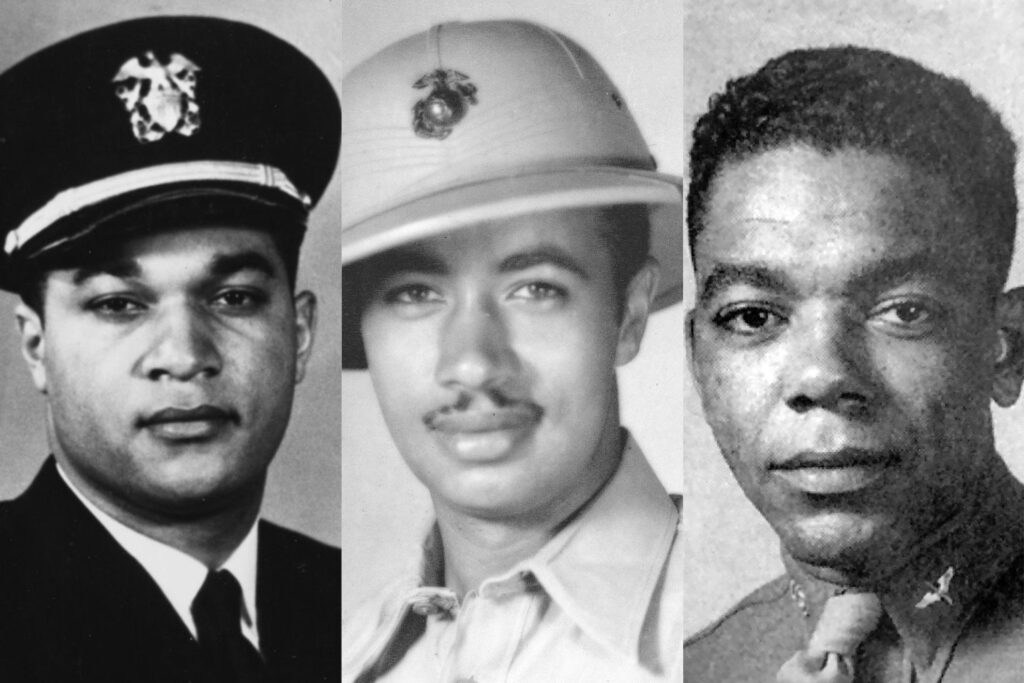

Also in the back building is the historical society’s celebration of local Black military heroes, those who served in the U.S. military.

Ettelson said the prominence of this story came as a surprise to the group’s researchers and they decided to make it its own gallery within the exhibit. The portion includes stories of Black soldiers fighting in segregated units during World War II, as well as biographies of men who fought for military desegregation, such as Glencoe’s Wilson Rankin Jr., one of the first Black Marines; Roger Brown, a Tuskegee airman; and Frank Sublett, one of the first commissioned Black officers in the Navy.

Rankin’s dress uniform and other Marine memorabilia are on display with his story.

The entire exhibit also includes commentary from numerous Black residents to form an oral history, as well as other historical documents, facts and items that help tell the story of Black heritage in Glencoe.

“We hope the exhibit as a whole will help educate people on our community and history of Black residents in our community, but also will help improve the relationship between the Black and white communities by increasing understanding of who we as a village have been throughout our history,” Ettelson said.

And Pastor K hopes it doesn’t stop in the halls of the Glencoe Historical Society.

“My greatest desire is this is the springing board to tell so many other untold stories that are wrapped into the tapestry woven into Glencoe,” she said, “and really change the perception that Glencoe and St. Paul AME Church are in the North Shore and it’s not as colorful and diverse as it is. I think we have the opportunity to be intentional about how everybody’s story is told.

“I’m excited about St. Paul being included but we want to help foster a platform that will tell so many other stories.”

The Record is a nonprofit, nonpartisan community newsroom that relies on reader support to fuel its independent local journalism.

Become a member of The Record to fund responsible news coverage for your community.

Already a member? You can make a tax-deductible donation at any time.

Joe Coughlin

Joe Coughlin is a co-founder and the editor in chief of The Record. He leads investigative reporting and reports on anything else needed. Joe has been recognized for his investigative reporting and sports reporting, feature writing and photojournalism. Follow Joe on Twitter @joec2319